The DHT: A Shared, Distributed Graph Database

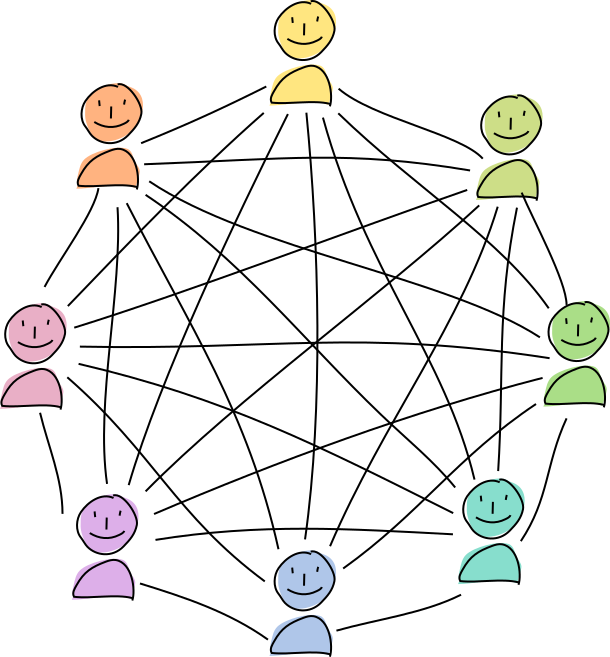

Agents share records of their actions, including any data meant to be shared with the group, in a distributed hash table (DHT). This database provides redundancy and availability for data and gives the network the power to detect and take action against corruption.

What you’ll learn

- The downsides and risks of self-owned data

- How public data is stored

- How nodes store and retrieve data in a distributed database

- What happens when the network falls apart

- How public data is validated

Why it matters

If you’re unsure whether a distributed network can provide the same integrity, performance, and uptime guarantees as a server-based system under your control, this article will give you a better picture of how Holochain addresses these issues. You’ll also have a better understanding of how user data is stored, which will help you think about how to design your persistence layer.

Self-owned data isn’t enough

Let’s talk about your source chain again. It belongs to you, it lives in your device, and you can choose to keep it private.

However, the value of most apps comes from their ability to connect people to one another. Email, social media, and team collaboration tools wouldn’t be very useful if you kept all your work to yourself. Data that lives on your machine is also not very available — as soon as you go offline, nobody else can access it. And it would disappear if your device were destroyed. So a peer-to-peer network needs a painless way to make shared data stick around when its author isn’t there.

This is also the point where we run into integrity problems in a peer-to-peer system. When everybody is responsible for creating their own data, they can mess around with it any way they like. In the last article, we learned that the signed source chain is resistant to third-party tampering, but not to tampering by its owner. They could erase a transaction or a vote and make it look like it never happened.

And finally, in cases where the validity of a given piece of data depends on a bunch of other data, it can be costly for someone to audit someone else’s data before deciding to engage with them. Because other people have probably checked portions of that same data, it’s possible to save everyone a bit of work by keeping records of the result of other people’s validation efforts.

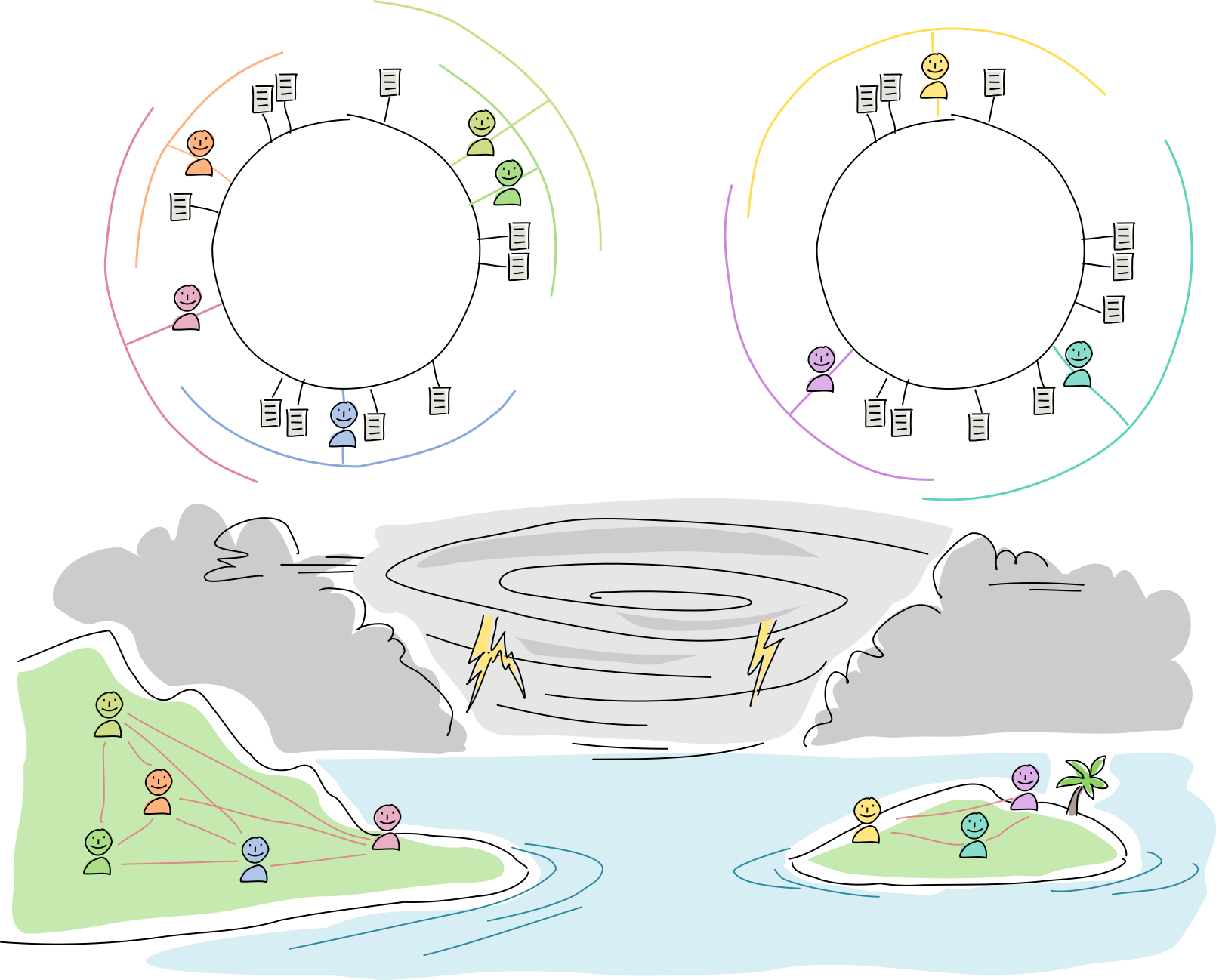

The distributed hash table, a public data store

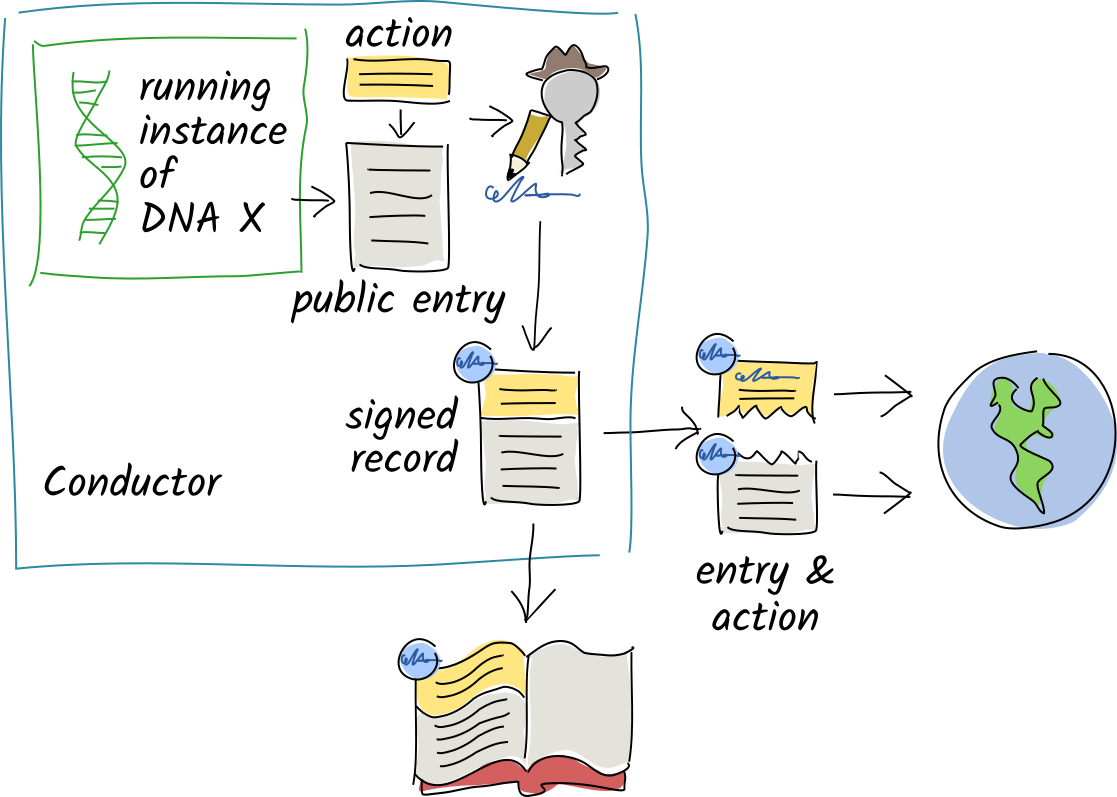

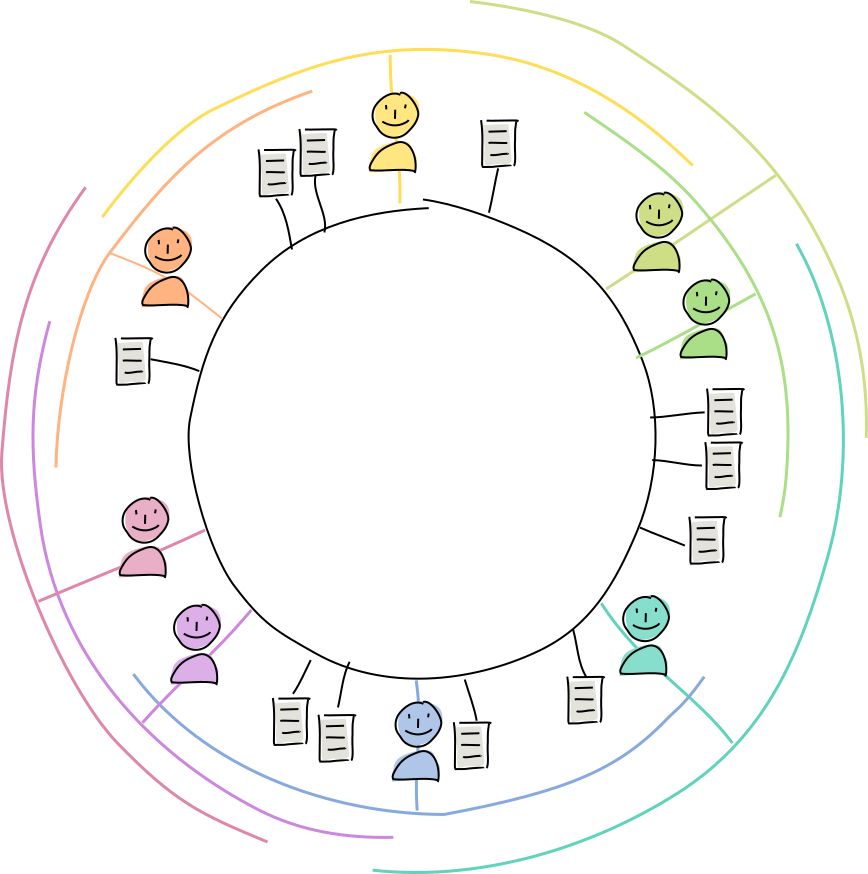

In a Holochain network, you share your source chain actions and public entries with a random selection of your peers, who witness, validate, and hold copies of them.

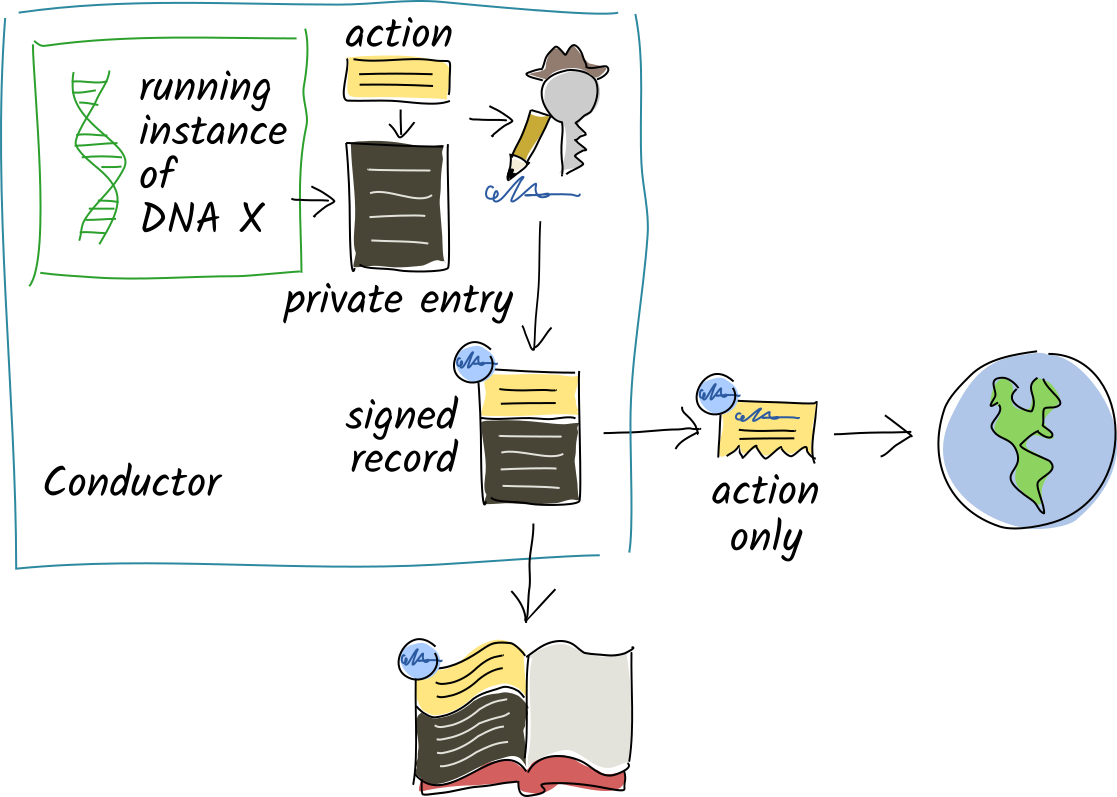

When you commit a record with private data, the entry data stays in your source chain, but the record’s action portion is still shared.

Every DNA has its own private, encrypted network of peers who gossip with one another about new peers, new data, integrity breaches, and network health.

This network holds a distributed database of all public data called a distributed hash table (DHT), which is a big key/value store with content hashes as keys and both record data and metadata as values. Each node holds a small shard of the DHT, so the burden of participation isn’t painful for any one agent.

Finding peers and data in a distributed database

Databases that spread their data among a bunch of machines have a performance problem: unless you have time to talk to each node, it’s very hard to find the data you’re looking for. DHTs handle this by assigning data to machines by ID. Here’s how Holochain’s implementation works:

- Each agent gets their own DHT address, based on their public key. Each piece of data also gets its own DHT address, based on its hash. These addresses are just huge numbers. And because they’re derived directly from the data they represent, they can’t be forged or chosen at will.

- Each agent chooses a section or ‘arc’ of the DHT neighborhood they want to be an authority for, as a range to the right of them in the DHT’s address space. They commit to keeping track of all the peers and storing all the data whose addresses fall in that arc.

- When an agent wants to publish or get a piece of data, they need to figure out who among their peers are most likely to be authorities for its address.

- The agent looks in their own list of known peers and compares those peers’ addresses against the data’s address.

- The agent sends their publish or get message to a few of the top candidates.

- If any of those candidates are authorities for that address, they respond with a confirmation of storage (for a publish) or the requested data (for a get).

- If none of the candidates are authorities, they look in their own lists of known peers and suggest peers who are more likely to be authorities. The agent then contacts those peers and the cycle repeats until authorities are found.

- If the request was a publish request, the authorities send a validation receipt back to the publisher and then ‘gossip’ the data to neighbors whose arcs also cover the data’s address, to increase redundancy.

Every peer knows about all of its closest neighbors and a few faraway acquaintances. Using these connections, they can find any other agent in the DHT with just a few hops. This makes it fairly quick to find the data.

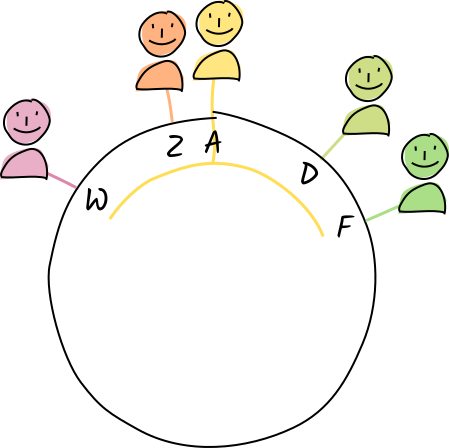

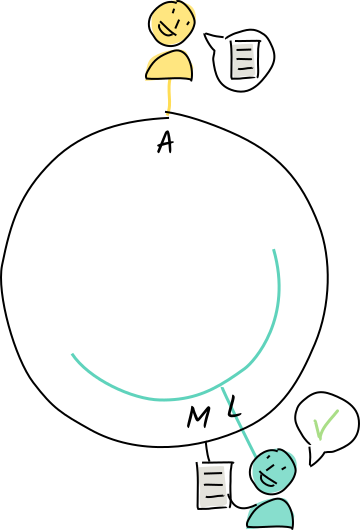

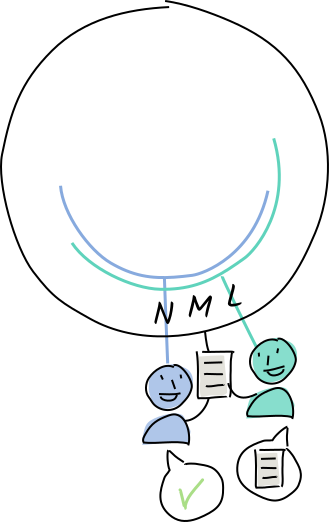

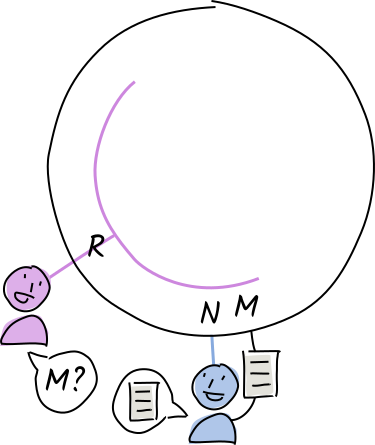

Let’s see how this works with a very small address space. Instead of public keys and hashes, we’re just going to use letters of the alphabet, where the first letter of a word is its address.

Alice lives at address A. Her neighbors to the left are Diana and Fred, and her neighbors to the right are Zoë and Walter.

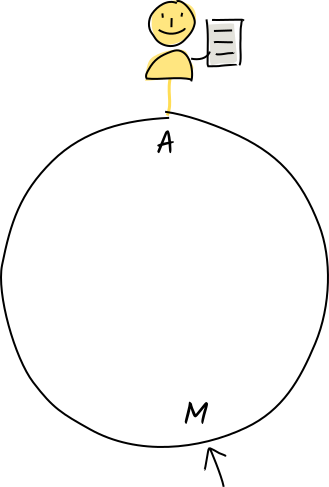

Alice creates an entry containing the word “molecule”, whose address is M.

Of all of Alice’s neighbors, Fred is closest to that address, so she asks him to store it. Fred hasn’t claimed authority for that address, so he tells Alice about his neighbor Louise.

Alice shares the entry with Louise, who agrees to store it because her neighborhood covers M.

Louise shares it with her neighbor, Norman, in case she goes offline.

Rosie is a word collector who learns that an interesting new word lives at address is M. She asks her neighbor, Norman, if he has it. Louise has already given him a copy, so he delivers it to Rosie.

Resilience and availability

The DHT stores multiple redundant copies of each piece of data so it’s available even when the author and a portion of the authorities are offline.

It also helps an application tolerate network disruptions. If your town experiences a natural disaster and is cut off from the internet, you and your neighbors can still use the app. The data you see might not be complete or up to date, but most of it is still accessible. Depending on how much of the DHT you’re personally storing, the app might even be useful when you’re completely offline.

Using information about their neighbors’ uptime, cooperating agents work hard to keep at least one copy of each entry around at all times. They adjust their arc size to ensure adequate coverage of the entire address space.

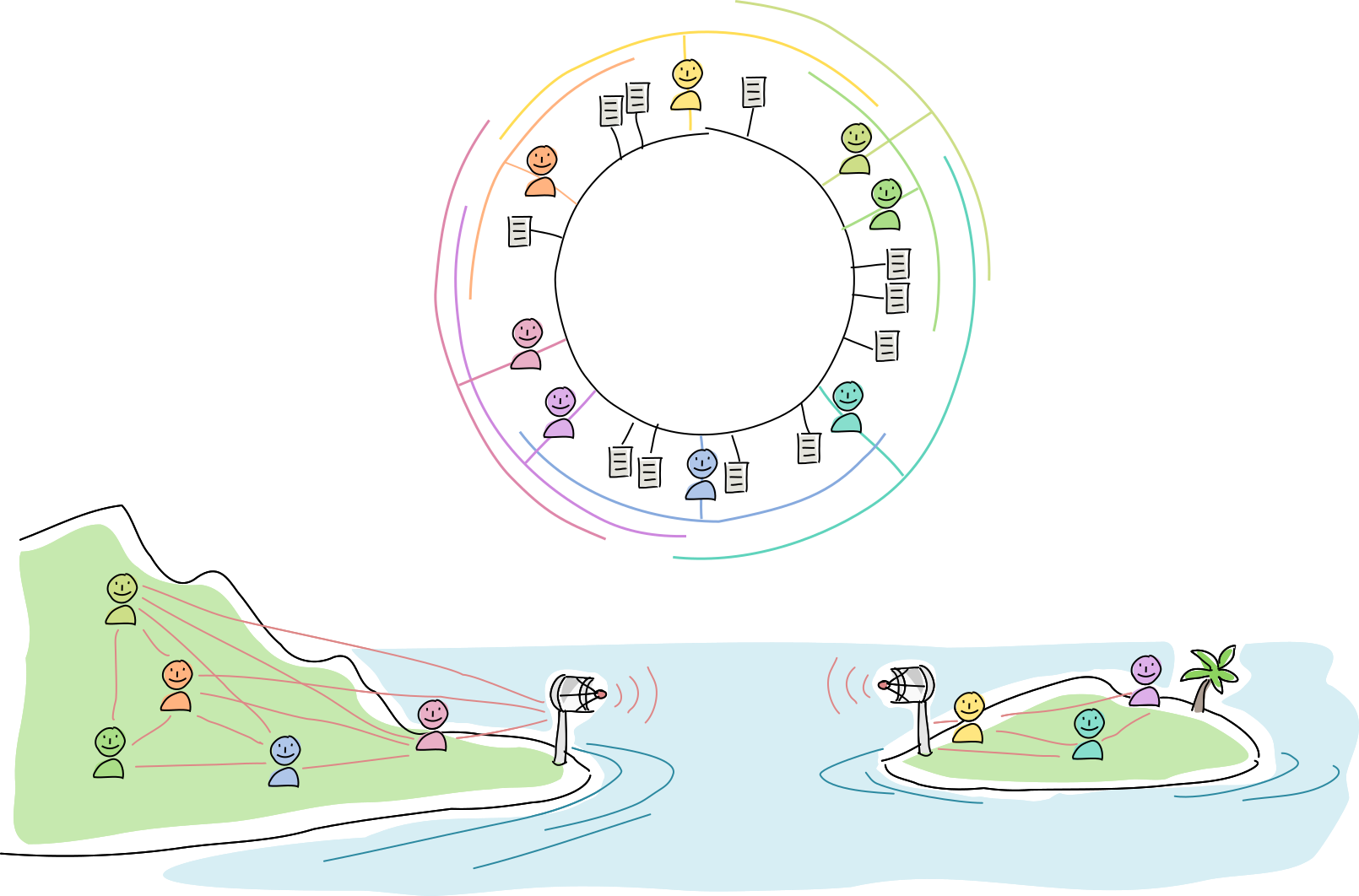

Let’s see how this plays out in the real world.

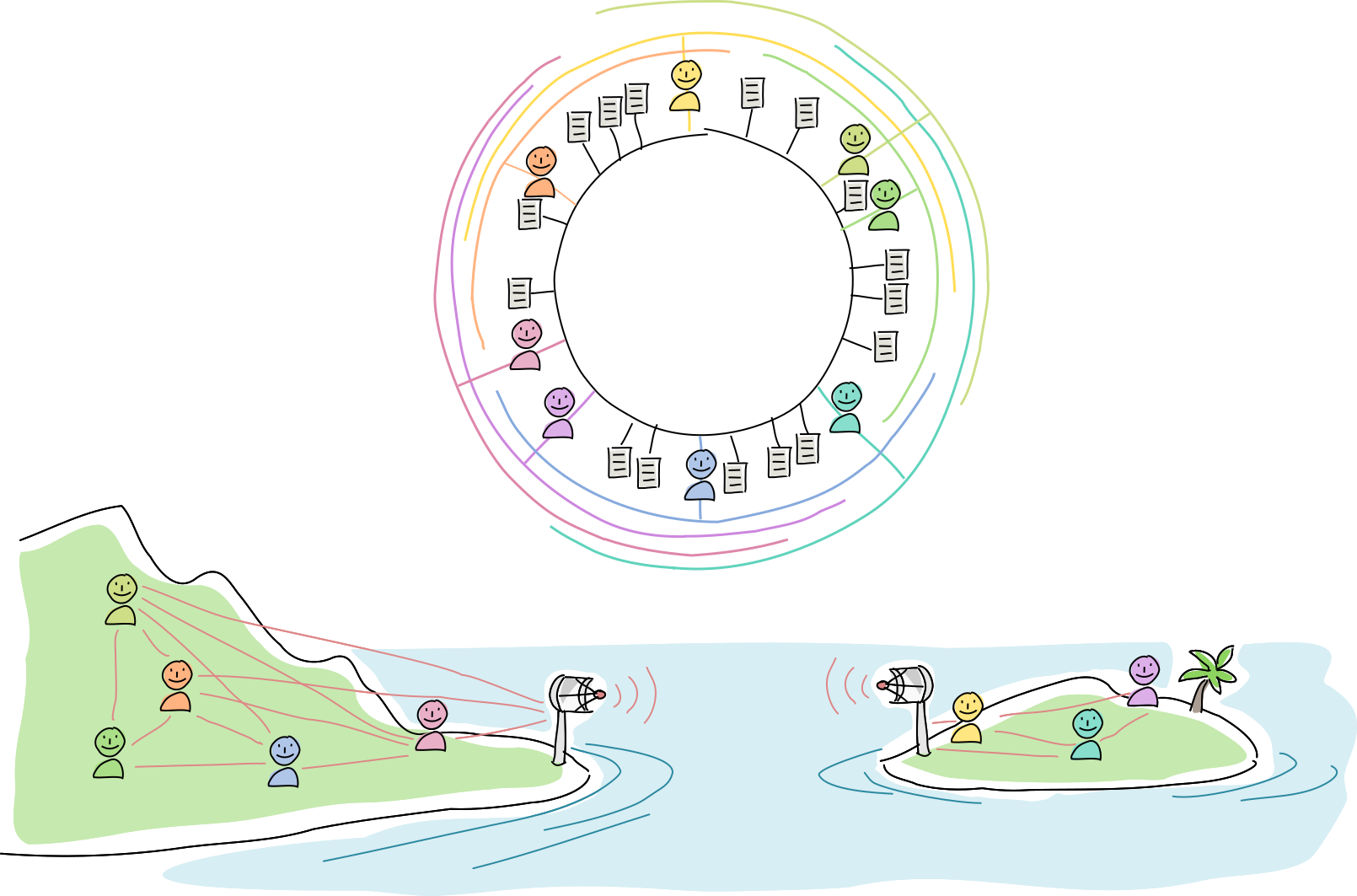

An island is connected to the mainland by a radio link. They communicate with each other using a Holochain app.

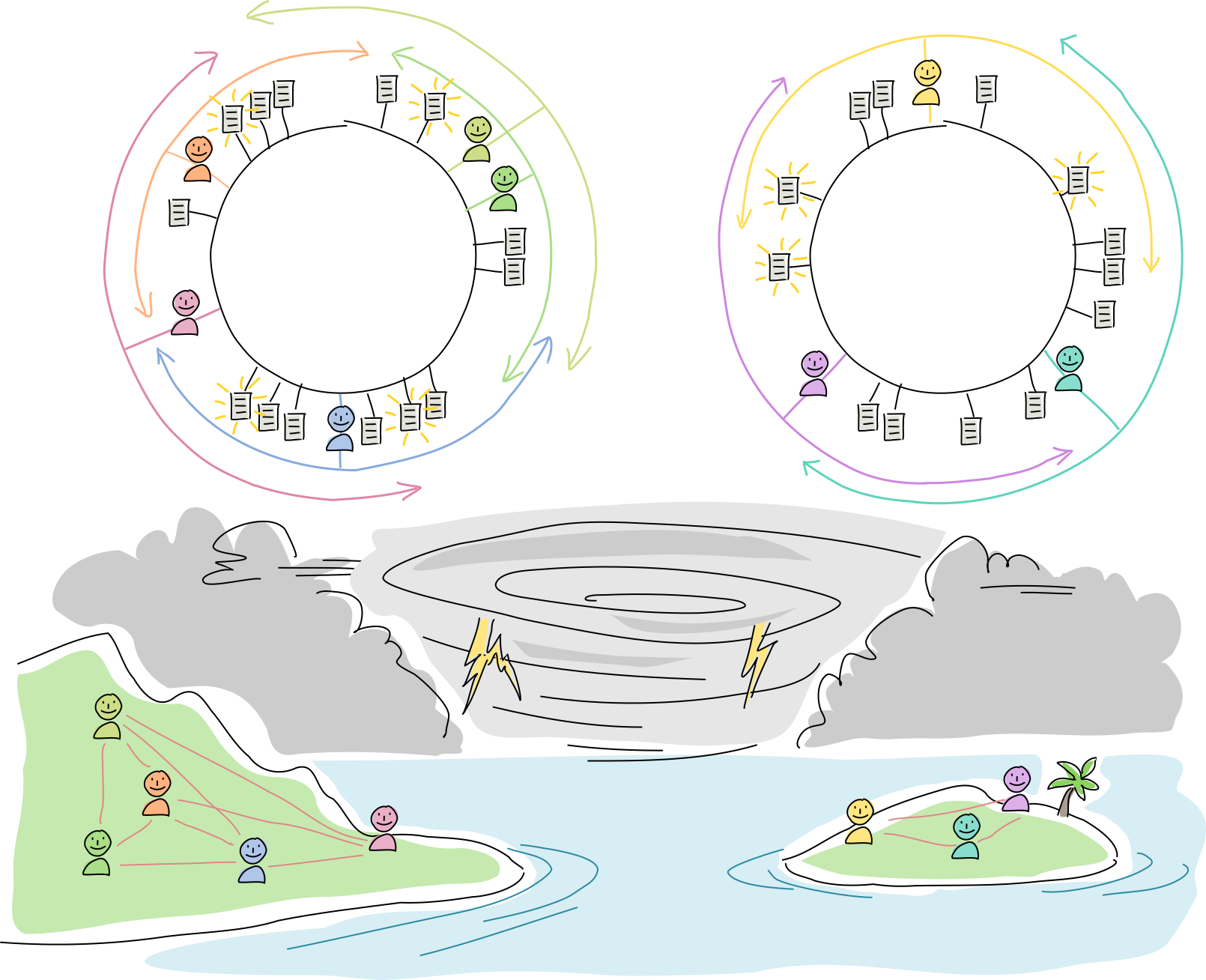

A hurricane blows through and wipes out both radio towers. The islanders can’t talk to the mainlanders, and vice versa, so some DHT neighbors are unreachable. But everyone can still talk to their physical neighbors. None of the data is lost, but not all of it is available to each side.

On both sides, all agents attempt to improve resilience by enlarging their arcs. Meanwhile, they operate as usual, talking with one another and creating new data.

The radio towers are rebuilt, the network partition heals, and new data syncs up across the DHT. At this point everyone has the option of shrinking their arc sizes and prune overly redundant data (although experience has shown them that it might be best to overcompensate in case another hurricane comes around).

A cloud of witnesses

When we laid out the basics of Holochain, we said that the second pillar of trust is peer validation. When a node is asked to store a piece of data, it doesn’t just store it — it also checks it for validity. As the data is passed to more nodes in its neighborhood, it gathers more signatures attesting to its validity.

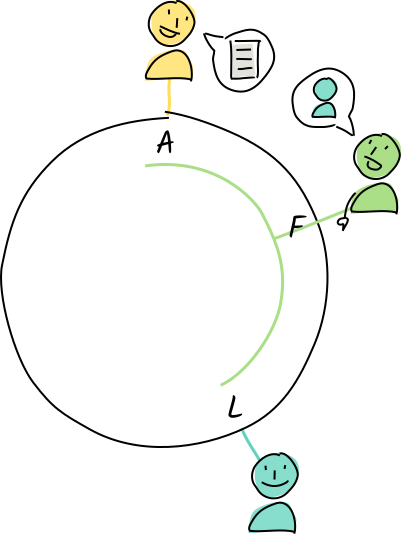

When an agent publishes a source chain record to the network, they don’t actually share the record itself. Instead, one or more DHT operations are produced. Those operations each have a location they’re sent to, a basis address. This is the DHT address we mentioned earlier. Once an authority receives an operation, they run the application-defined validation function against the operation, either accepting it, rejecting it, or marking it for retry if not all information it depends on is available. If it passes, the authority will ‘integrate’ it into their slice of the DHT, which means that they’ll apply the operation to transform some of the data at the basis address in their little piece of the key/value store.

Let’s see what happens when a simple ‘create entry’ record is published to the DHT.

- A store entry operation, containing both the entry blob and the create-entry action, goes to the entry authorities whose arcs cover the entry hash. When it’s integrated, the authorities will hold the entry data at that basis, along with metadata that contains the action.

- A store record operation, containing the entry and the action, goes to the record authorities whose arcs cover the action’s hash. When it’s integrated, the authorities will hold the action at that basis address.

- A register agent activity operation, containing the action, goes to the agent activity authorities, peers whose arcs cover the author’s public key. When it’s integrated, the authorities will add the action to a copy of the author’s source chain.

No matter what operation they receive, all three authorities check the signature on it to make sure it hasn’t been modified in transit and it belongs to the agent that claims to have authored it. If the signature check fails, the data is rejected.

After this first check, the authorities run the data through the proper system and app-level validation rules, then sign the result and return it to the author as a validation receipt.

If validation fails, the validator also generates a warrant, which is a signed proof that the author has broken a rule. They then publish this warrant to the agent activity authorities, who keep the warrant on file. Any peer who receives a warrant, either via gossip or by requesting invalid data, validates it against the data that’s claimed to be invalid, then blocks network communications with the warranted author. This is what creates Holochain’s immune system.

Using cryptographically random data (public keys and hashes) as addresses has a couple benefits. First, validator selection is impartial, resistant to collusion, and enforced by all honest participants. Second, the data load is also spread fairly evenly around the DHT.

Detecting attempts to rewrite history

Now we’ll explore how the DHT catches those who attempt to rewrite their source chain. Because every action produces an agent activity operation which is supposed to get sent to the same group of peers (the agent activity authorities), they can check your entire history to see if you’ve already published an action that shares a previous action hash and chain sequence number with the one you’re trying to publish. This data then becomes available to anyone who asks.

The important thing is that your peers in the DHT remember what you’ve published, so it’s very hard to break the rules without getting caught.

Key takeaways

- Source chain entries can be private (kept on the user’s device) or public (shared in the DHT). Source chain actions are always public. Participants share these with their peers in a distributed database called the DHT.

- A piece of data in a DHT is retrieved by its unique address, which is based on its hash.

- Each participant takes responsibility to be an authority for validating and storing a small portion of the public data in the DHT, informing their peers of the range of addresses they’re taking responsibility for.

- Peers in Holochain’s DHT validate all data they store, sharing validation results with peers who ask for the data. This speeds things up for everyone and allows rapid, efficient detection of bad actors.

- Holochain’s DHT also detects agents’ attempts to modify their source chains.

- Authority selection for a piece of data is random and enforced by all honest peers.

- A negative validation outcome produces a warrant, which attests that an agent has broken the rules.

- Possessing a warrant lets a peer justify taking action against the subject of the warrant, such as blocking them.

- Warrants spread around the network, creating an ‘immune system’ response.

- A DHT tolerates network disruptions. It can keep operating as two separate networks and subsequently ‘heal’ when the network is repaired.