Application Architecture

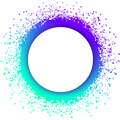

Applications built with Holochain are highly modular. This makes it easy to share code and compose smaller pieces together into larger wholes. Each functional part of a Holochain application, called a DNA, has its own application logic, isolated peer-to-peer network, and shared database.

What you’ll learn

Why it matters

A good understanding of the components of the tech stack will equip you to architect a well-structured, maintainable application. Because Holochain is probably different from what you’re used to, it’s good to shift your thinking early.

Agent-centricity

Perhaps Holochain’s most important difference is that applications are completely centered around the individual — and, because it’s made for networked applications, around groups of individuals. The purpose of a Holochain application is to create a network where people (or bots) can interact freely with each other, playing by a shared set of rules. This is possible because everyone, whether human or bot, is running their own copy of the application and connecting directly to their peers.

So the term ‘user’ doesn’t feel quite right for Holochain, where the ones who use the application are also the ones who keep it alive. Let’s call them ‘agents’ — or better yet, ‘participants’. We’ll also sometimes call their devices ‘nodes’ or ‘peers’ when they’re operating within a network.

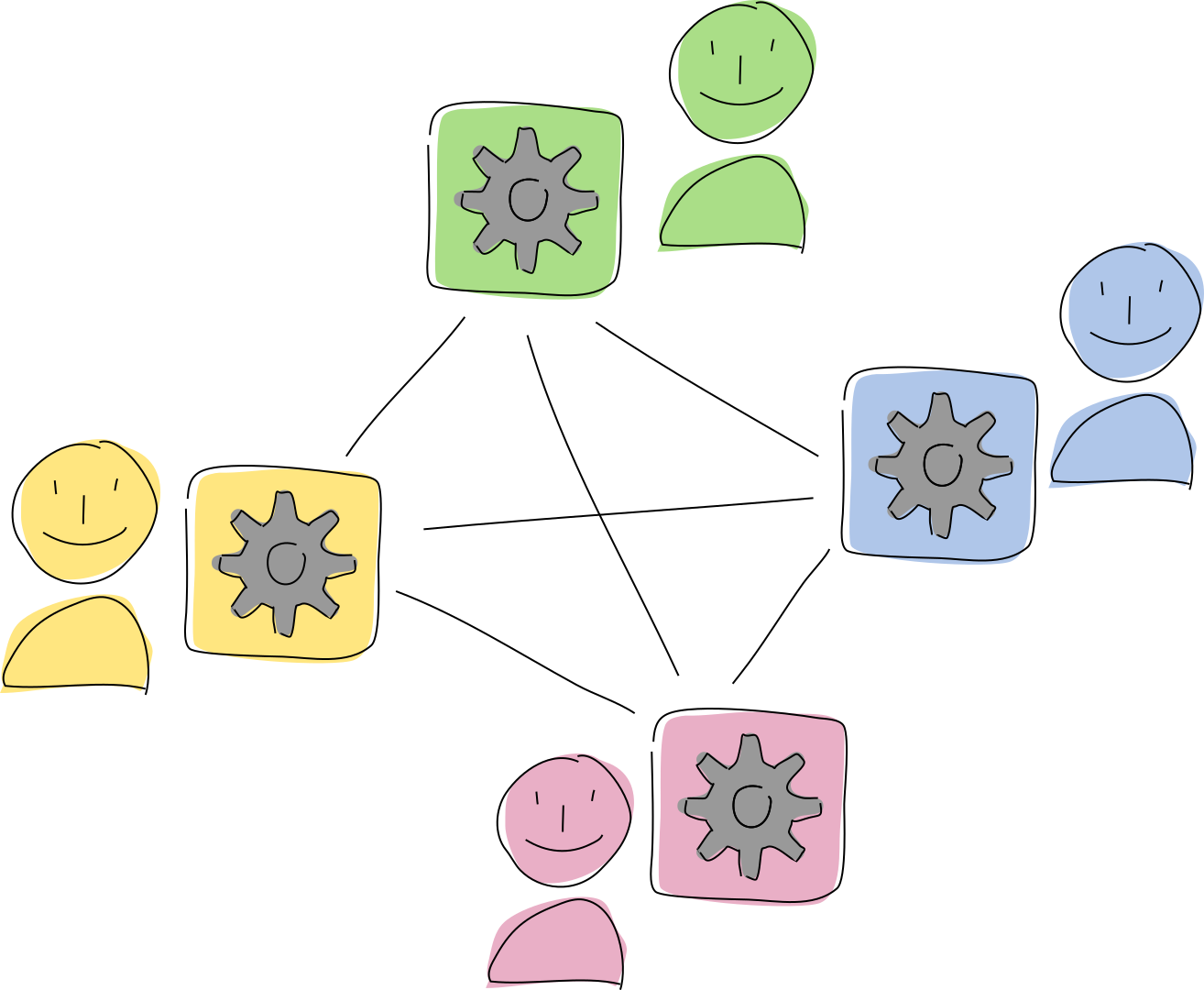

How do you know other participants are playing by the same rules as you? As we explored in The Basics, all you have to do is look at the data they create and share. If their data doesn’t pass your copy of the rules, they’re playing a different game and you should ignore them.

These data integrity rules create a membrane between a participant and her peers. They define what data she can and can’t create, and they help her recognize rule-breakers.

There’s another membrane, which sits between a participant and her copy of the application. The application’s public functions define the processes that can be used to access, interpret, and create data, as well as communicate with other participants and applications. Her copy of the application makes those functions available to any client on her machine that wants to act on her behalf, such as a UI or a scheduled script. Those functions are also made available to her peers in the same network so she can delegate some of her agency to them. The application developer can give her tools to control access to these functions using capability-based security.

Layers of the application stack

Holochain handles a lot of things for you, keeping your development workload minimal and mostly focused on the problems you need to solve. You rely on Holochain for things like data persistence and networking, and get on with building your data model and application logic.

Now, let’s get into the details of all the components of a Holochain app, and how they fit together.

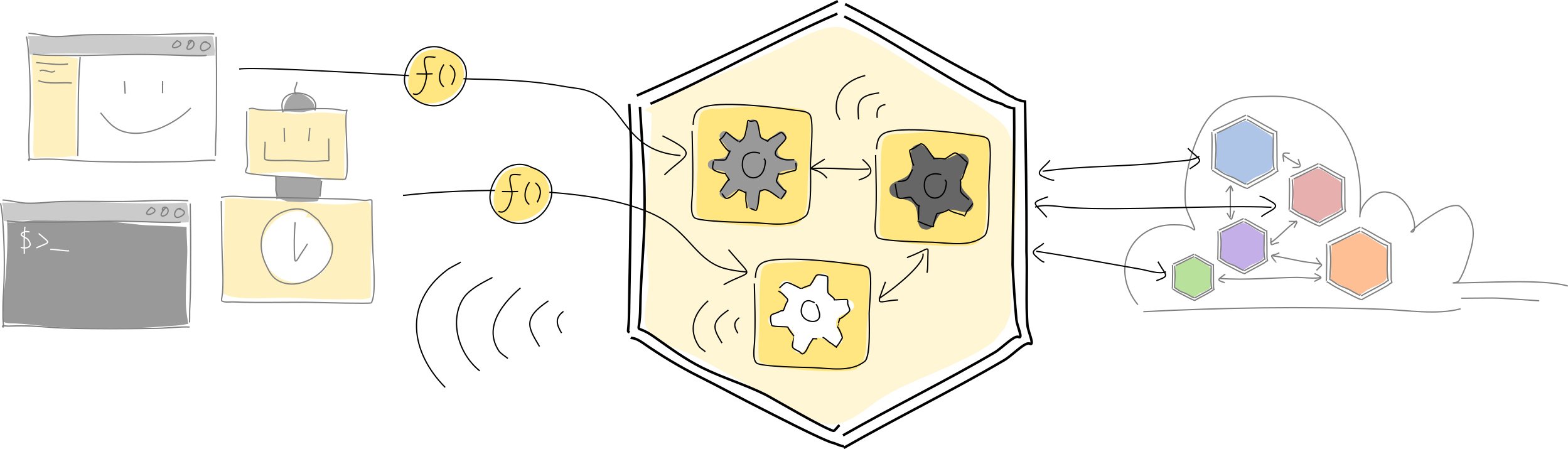

At a glance

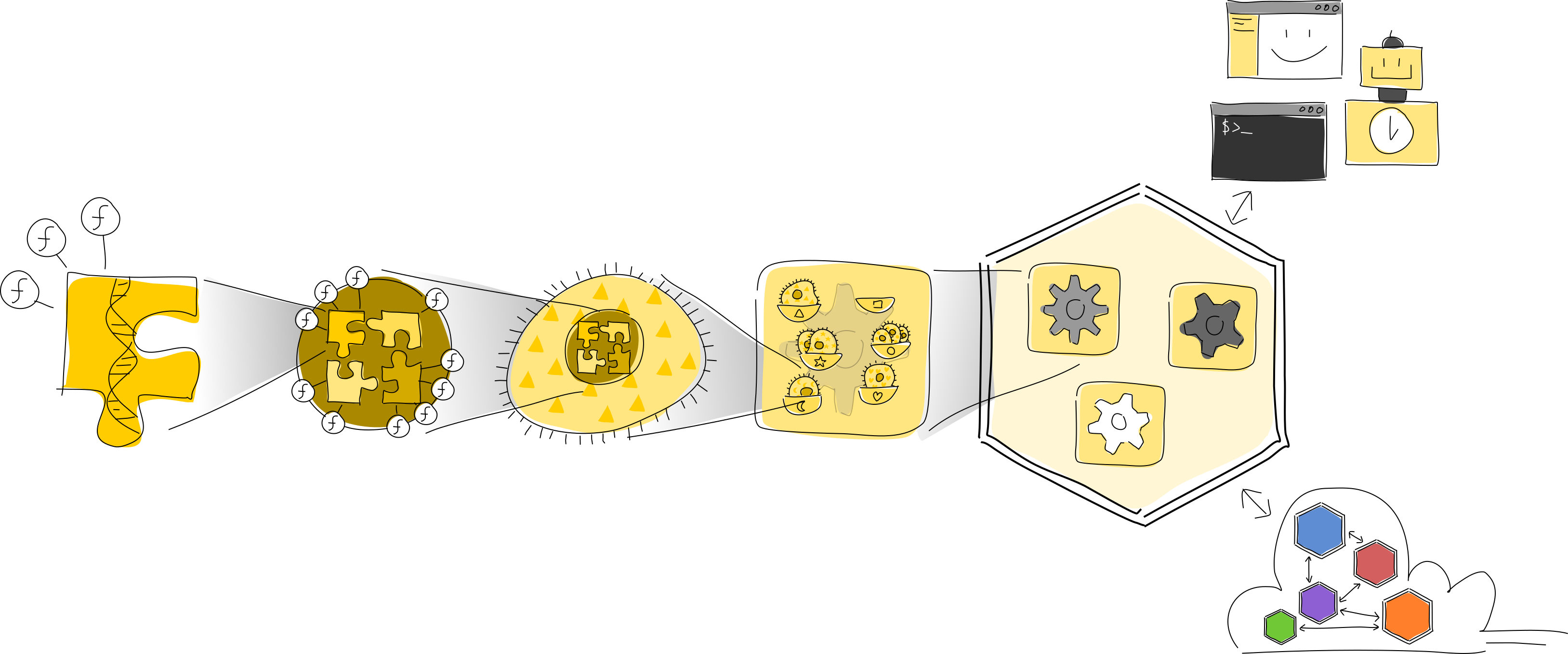

Now let’s quickly introduce all the terms, so you’re familiar with them when you encounter them. A client running on a participant’s device talks with their conductor, which runs multiple hApps. Each hApp is made of one or more cells, which are the live instances of DNAs that run on behalf of the participant. These DNAs, in turn, are made of one or more executable zome modules. (Don’t worry; it’ll make sense as we dig in.)

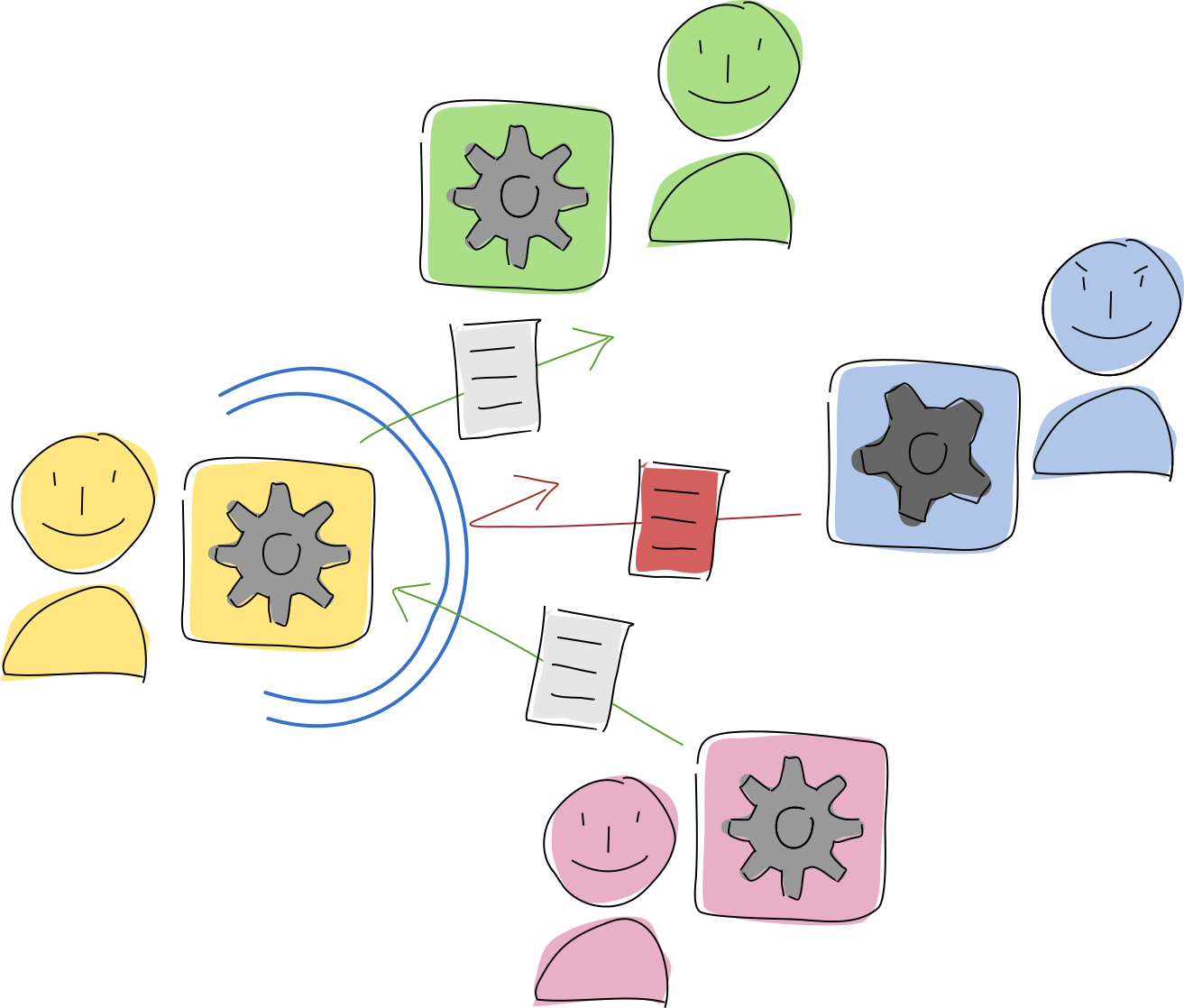

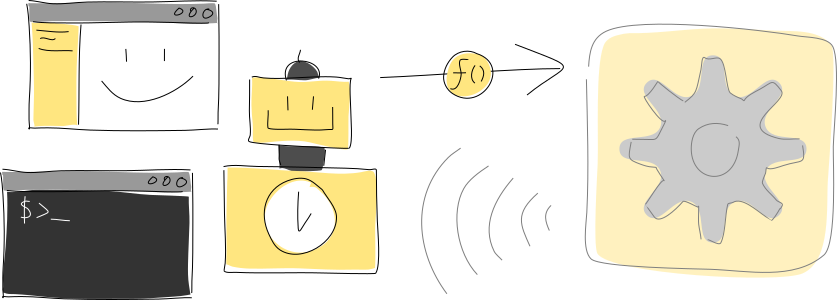

Client

A client on the participant’s device, such as a UI or utility script, talks to their Holochain conductor and its running hApps via remote procedure calls (RPCs) over WebSocket. A hApp can also send signals back to the client; signals are useful for real-time event notifications.

The client is like the front end of a traditional app and can be written with whatever language, toolkit, or framework you like. One hApp can have multiple clients, and one client can talk to multiple hApps. You can even make a headless client, like a shell script or scheduled task. This client and its related hApp make up a complete application.

Conductor

The hApp is hosted in the participant’s conductor. It’s the runtime that sandboxes and executes hApp code, handles cryptographic signing, manages data flow and storage, and handles connections both locally with clients and remotely with peers. When the conductor receives a function call, it routes it to the right function in the right hApp.

In some ways, you can think of the conductor as a web application server, except that runs on every participant’s device. It also has a lot more responsibilities — not only does it handle local communication with clients, but it also acts as both a server and a client amongst other peers using the same application network. It’s handling a lot of things simultaneously, which is why we call it a conductor.

The conductor also has a keyring which manages the participant’s cryptographic identities, which are made of public/private key pairs.

hApp

A Holochain application or hApp is a bundled suite of functionality, such as chat, accounting, or project management. A hApp is often made of multiple components, each providing an aspect of functionality or ‘role’.

Cell

Cells fill roles in a hApp. Each cell is a combination of a participant’s unique cryptographic key pair (their agent ID) and a DNA. Within one participant’s instance of a hApp, all cells share the same agent ID. Each cell acts as the participant’s personal agent — every piece of data that it creates or message it sends, it does so from the perspective of that agent.

Each cell stores its own agent history and is a member of an isolated network along with other cells that share the same DNA. This is useful for creating separate spaces inside a single hApp — individual project workspaces or private chat channels, for example.

As a bundle of running code, a cell exposes the functions you write as its public API, which can be accessed by other cells within the same hApp, clients on the same machine, or other cells on the network that the cell belongs to. When a client or other cell calls a function in a hApp, it specifies the cell ID, which is the hash of the DNA plus the agent ID, along with the zome name, function name, and function input payload. The developer can give a participant the ability to control access to their cell’s API via capabilities.

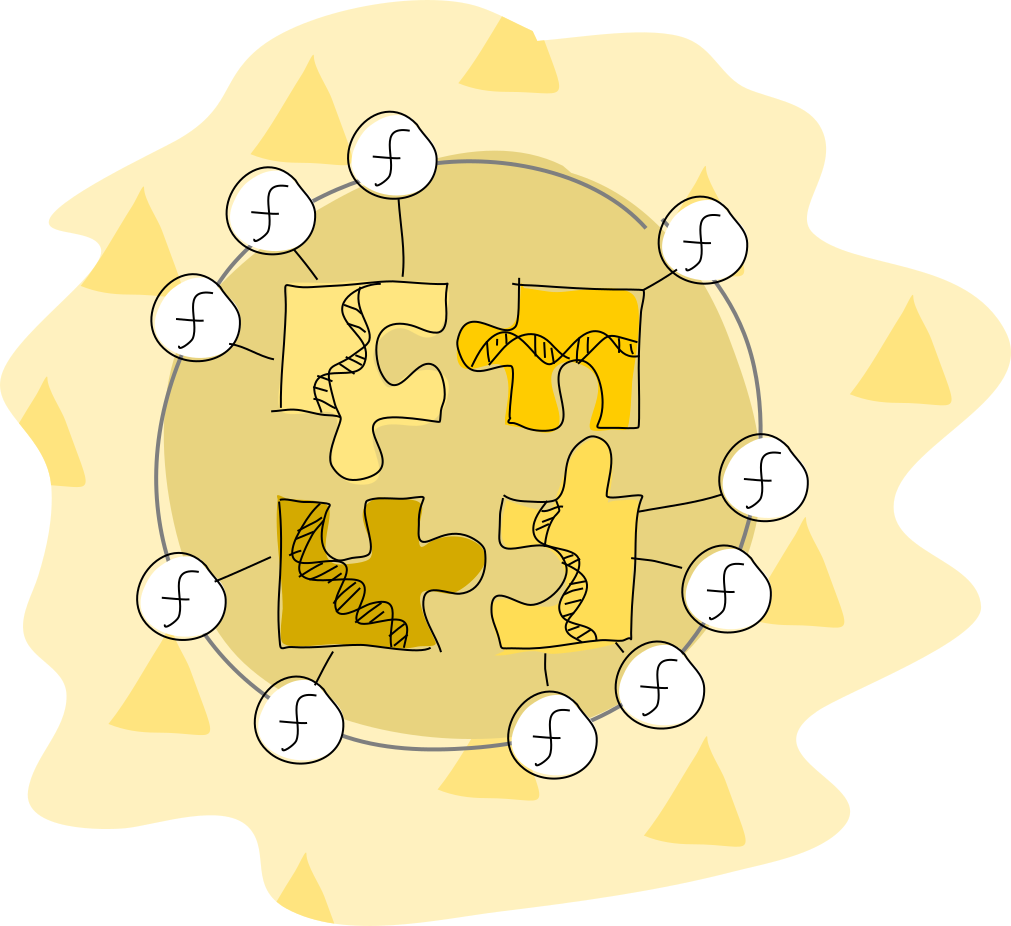

DNA

The bundle of executable code running in a cell is called a DNA. You can think of it like a microservice that creates an access and integrity layer around personal and shared data. It serves as the ‘rules of the game’ against which peers can do validation and enforcement. Each DNA implements the code that fills a particular role in a hApp.

The DNA can also contain metadata: a name, description, network seed, and properties. These can be changed either in a text editor or at installation time. When the network seed is changed, it clones a DNA, creating a new cell with identical code but an entirely separate history, network, and shared database. Properties can affect the new cell’s runtime behavior (similar to configuration parameters or environment variables), and changes to properties also cause the DNA to be cloned.

A clarification on cells and DNAs

If you’re finding it hard to keep cells and DNAs separate in your mind, remember that a DNA provides the code for a cell, while a cell is a running instance of a DNA, bound to an agent ID. Otherwise, what can be said of a DNA can also be said of a cell.

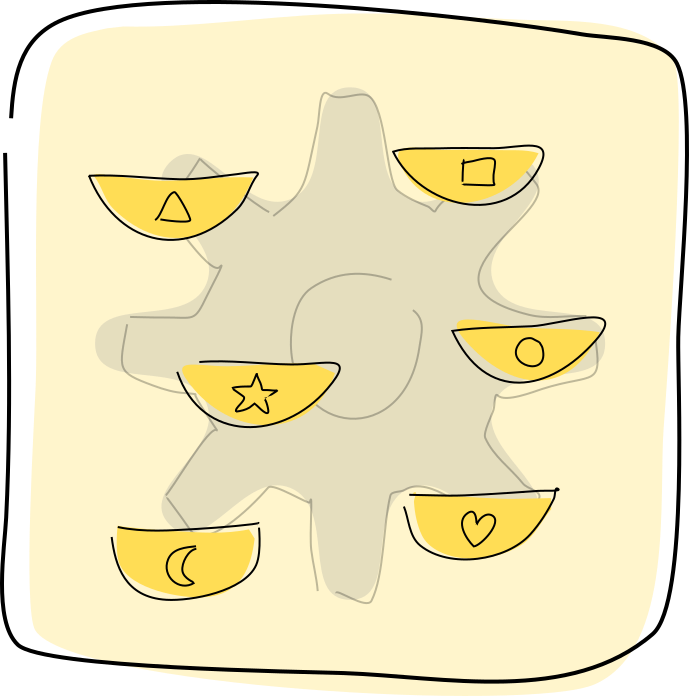

Zome

The executable code modules in a DNA are called zomes (short for chromosomes), each with its own name like profile or chat. The zomes define the core logic in a DNA.

There are two kinds of zomes:

- Integrity zomes define data types and a validation function that checks writes of those types for correctness. You can think of them as fully programmable database schemas that access to a participant’s current application state and even portions of shared application state. They have limited access to the conductor’s host API, just enough to pull in external data and perform basic cryptographic functions.

- Coordinator zomes implement application logic, including the DNA’s public API. They can also define callback functions that handle cell lifecycle events such as startup, scheduled task events, and post-write follow-up. Coordinator zomes have access to a much broader range of the conductor’s host API, including the ability to call the public APIs of other cells in the conductor and across the network, send signals to listening clients, and schedule tasks.

All of these functions are run from the perspective of the individual participant. When a function is called for Alice, it’s called in her own cell in her machine, writing data to her personal store. Unlike with cloud and blockchain, there is no objective third party that runs application code. Things happen only when someone causes them to happen on their own machine.

Consider source code and configuration changes carefully, because each modification to an integrity zome will result in a new DNA with new cells interacting in a separate network. This may require some sort of migration strategy to move or access data between old and new cells.

Coordinator zomes aren’t subject to the same strict rules, and can be swapped for new ones in a running cell. Care must still be taken, however, because each participant is free to swap coordinator zomes as they like (or more realistically, as the hApp developer gives them the power to), so an entire network of cells isn’t guaranteed to be running the same coordinator code. This can cause subtle compatibility differences between different versions of your coordinator zomes’ code.

DNA Memory State

All functions in your DNA start with a fresh memory state which is cleared once the function is finished. The only place that persistent state is kept is in the participant’s personal data journal. If you’ve written applications with REST-friendly stacks like Django and PHP-FastCGI, or with function-as-a-service platforms like AWS Lambda, you’re probably familiar with this pattern.

In summary

That’s the entire stack of a Holochain hApp. Let’s review, this time from the inside out:

- A zome is a module that contains executable code and exposes some of its functions as an API. Integrity zomes define data types, while coordinator zomes define core application logic.

- One or more zomes are bundled into a DNA, which is like a microservice that defines all the rules for a given network.

- A DNA comes alive as a cell bound to an agent ID, running on behalf of a participant.

- One or more cells are slotted into roles in a hApp, which makes up an application’s back end.

- A participant’s conductor hosts the hApps she uses, mediating local and network access to them and executing their code.

- The participant’s clients access the hApp via the conductor’s local RPC interface, while the conductor also allows the hApp to communicate with other participants’ cells that belong to the same networks.

Key takeaways

You can see that Holochain is different from typical application stacks. Here’s a summary:

- An application consists of a client and a hApp (a collection of separate microservices called DNAs which in turn are composed of code modules called zomes) running on the devices of all participants.

- The hApp runs in the conductor, Holochain’s application server runtime.

- The conductor sandboxes the DNA code, mediating all access to the device’s resources, including networking and storage.

- All code is executed on behalf, and from the perspective, of the individual user.

- A DNA is instantiated into a cell for each user on their device. Each cell has its own history and belongs to a separate private network shared by all cells using the same DNA.

- A DNA’s data model and application model are separated into integrity zomes and coordinator zomes.

- Some attributes of a DNA — its integrity zomes, network seed, and properties — are considered DNA modifiers. They contribute to the DNA’s unique ID, and changes to these attributes result in a ‘cloned’ DNA whose cells live in a separate network from the original DNA.

- Other attributes of a DNA — its coordinator zomes — can be swapped out without causing the DNA to be cloned.

- Users communicate and share data directly with one another rather than through a central server or blockchain validator network.

- Holochain is opinionated about data — it only provides one storage implementation. (We’ll learn about what, why, and how in the next three articles.)

- Zomes don’t maintain any in-memory state between calls; state is maintained in the history of the cell that contains the zome.

- At its heart, Holochain is a framework for validating and manipulating shared data. However, you usually don’t need a lot of your application logic in your DNA — just enough to encode the ‘rules of the game’ for your application.

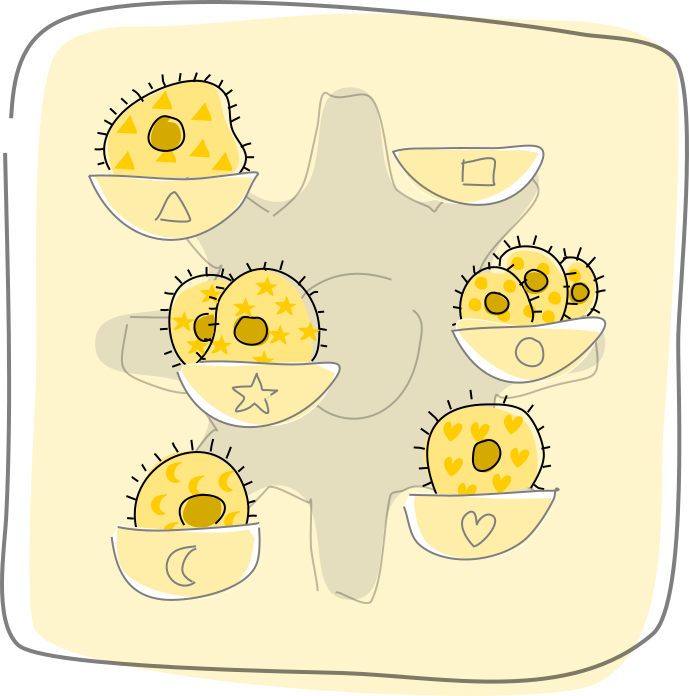

- Holochain lends itself to combining small, reusable components into large applications.