Countersigning: Reaching Agreement Between Peers

Unstable feature

This feature is considered unstable and is disabled by default in Holochain 0.4 and newer. It may be removed or changed in future versions of Holochain. If you want to enable it, read the advice on the 0.4 upgrade guide.

What you’ll learn

- Differences between Holochain, client/server, and blockchain

- How countersigning works

- How to nominate a witness to prevent collusion

- How to nominate multiple witnesses

- What countersigning doesn’t do

Why it matters

A lot of human interactions involve formal transactions of one sort or another. These are usually conducted in a peer-to-peer way — that is, as an exchange of information among the people who are directly involved. Payments, legal agreements, property transfers, and even chess moves require parties to reach a shared understanding of the states of one another’s worlds, then coordinate a shared change to those states. Because this is such a common pattern, we built it right into Holochain.

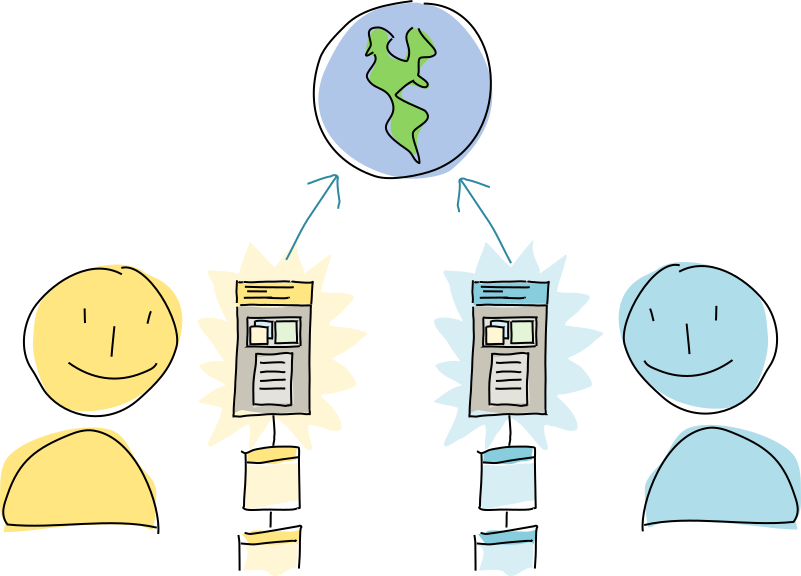

Agreement versus consensus

If you’re familiar with client/server or blockchain architectures, you might be surprised that Holochain doesn’t attempt to maintain a consensus about global state. As you saw when you learned about the source chain, each participant is responsible for their own local state.

It might sound messy, but it’s how the real world works. When we’re busy about our day, we don’t constantly check a public “record of everything everyone did” to make sure we’re not getting in each other’s way. We just do things. And when we want to coordinate our actions with other people, we arrange it with them directly.

We believe that, for the vast majority of applications involving transactions, this — plus witnessing by a selection of random peers — is all that’s needed.

Holochain lets you do this through countersigning. In this process, two or more parties agree on the contents of a single entry, then write that entry to all of their chains within an agreed-upon time period. It’s hard to manage the communication necessary for reaching a reasonable level of atomicity, so that’s why it’s built into the framework rather than being something you have to build yourself. The human agreement on the content beforehand, and some of the data transfer steps, are left for you to build however you like. But the core of the functionality — in which everybody does their best to make the commit atomic for all counterparties’ source chains — is all provided.

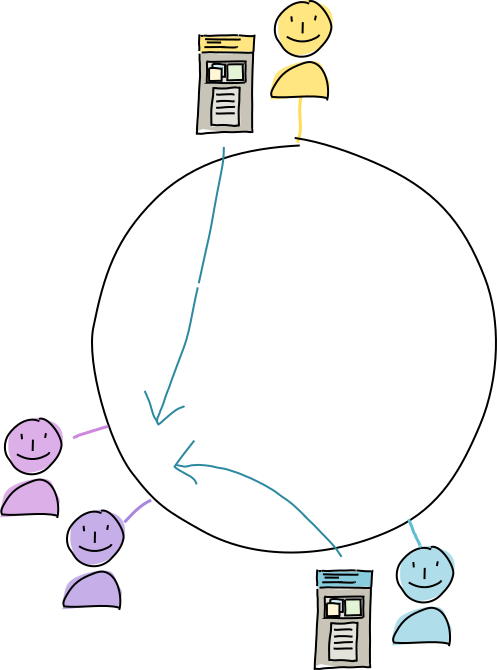

The countersigning process

In order to safely coordinate the writing of a single new action to both of their source chains, Alice and Bob have to be able to:

- Lock their source chains at an agreed-upon point,

- Check that the action to be written will be valid from the perspective of both of their states,

- Tentatively publish the action in a way that lets them back out if something goes wrong,

- Wait for evidence that the other party has done the same thing, and

- Complete the write and permanently publish the whole thing to the DHT if everything’s successful, or back out if it’s not, and

- Unlock their source chains.

Here’s a more in-depth look at this process. Keep in mind that it’s meant to be an automated process, finished within a few seconds while Alice and Bob are both online. Any human agreement (such as negotiating meeting times, contract terms, or transaction amount) should happen beforehand.

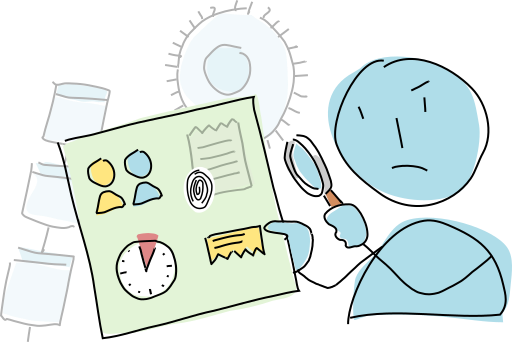

Alice and Bob exchange the details needed to create the entry that will be countersigned.

Alice creates a preflight request containing:

- The parties involved (her and Bob in this case)

- The hash of the entry that will be countersigned

- The time window in which the countersigning must complete

- A stub of the action to go along with the entry, which contains its action type and entry type (currently create-entry and update-entry actions can be countersigned; in the future delete-entry, create-link, and delete-link actions will be too)

- Optional arbitrary application data

Alice sends the preflight request to Bob for approval. (You can implement this any way you like, but a remote call is probably the best.) At this stage, it’s expected that Bob is able to independently construct the data that will go into the countersigned entry, based perhaps on his history with Alice or the optional application data, to determine whether the request is something he wants to accept. Acceptance could be automated, or it could request Bob’s intervention via a signal to his UI.

Bob’s conductor attempts to accept the preflight request, which involves checking whether it is possible to write a countersigned record (that is, there are no incomplete countersigning sessions or pending source chain writes, and Alice’s specified time window doesn’t conflict with Bob’s system clock). If everything looks good, Bob’s conductor locks his source chain.

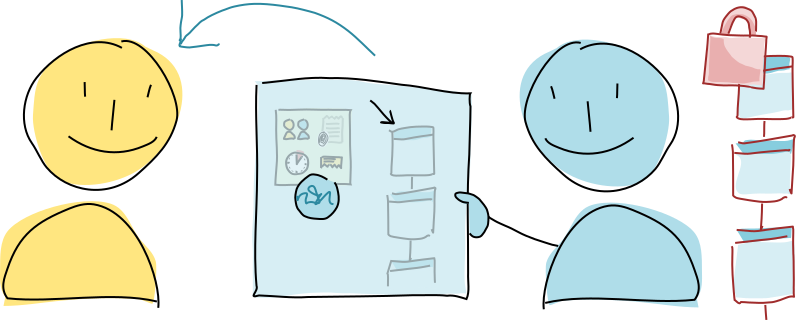

Bob’s conductor produces a preflight response, containing his signature on the request and the record ID at which his source chain is currently locked. Bob sends this preflight response back to Alice.

Alice receives Bob’s preflight response, then tries to generate a preflight response herself from the request she created. Now her own source chain is locked as well.

Alice compiles both the preflight responses into a countersigning session structure, containing the original agreed-upon preflight request and all the responses. She shares it with Bob (again, this could be done with a remote call).

Alice and Bob both create the entry to be countersigned on their own machines, which contains both the countersigning session data structure and the app data they’d previously agreed on. Then they do a trial run of committing the entry.

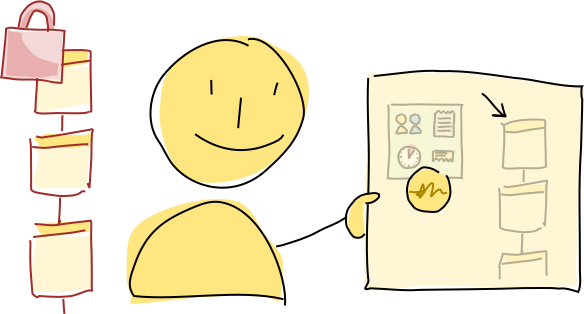

At this point Alice and Bob’s conductors take over completely from the cells. As with any commit, they attempt to validate the new action. But with a countersigned action, each participant’s conductor validates it multiple times — once from their own perspective, and once from the perspective of all the other parties. This is possible because Alice and Bob both have the same countersigning session data structure, which contains the current states of both of their source chains. If this step didn’t happen, DHT validating authorities would warrant all parties for neglect, not just the one for whom the action was invalid.

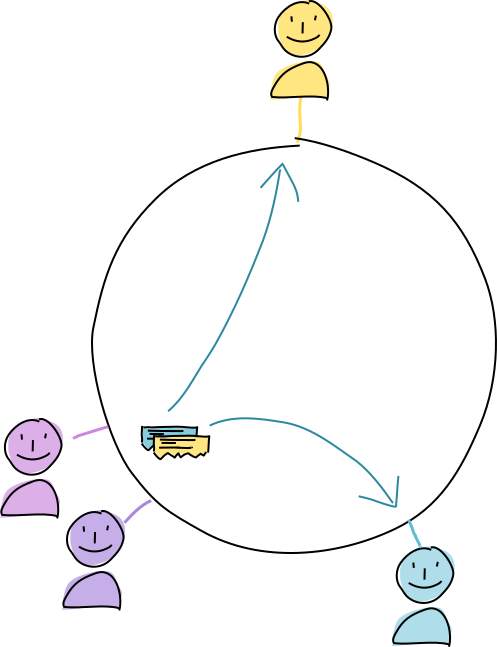

Once validation is finished, Alice and Bob both do a trial run of publishing the operations generated by the new action to the DHT — but only the store entry operations. The authorities collect the data but don’t integrate it into their DHT stores; right now they’re simply acting as witnesses who wait until they’ve seen the operations from both Alice and Bob.

Once the authorities have collected all the data, they send the full set of actions back to both of them.

Timeouts

If Alice and Bob reach the end of the time window without receiving this action set, their conductors discard the new action and unlock their source chains as if nothing had happened. Likewise, the authorities discard the pre-published data if they don’t collect all the required signatures within the time window. There is no built-in feature to retry an expired session, but it could be built into the application.

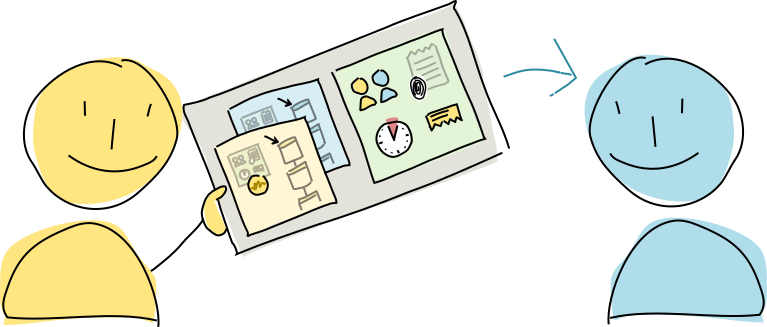

When Alice and Bob’s conductors each receive the full set of actions, they finally unlock their source chains, commit the actions, and publish all the resulting operations to the DHT as normal. This creates a permanent, public record of all parts of the transaction.

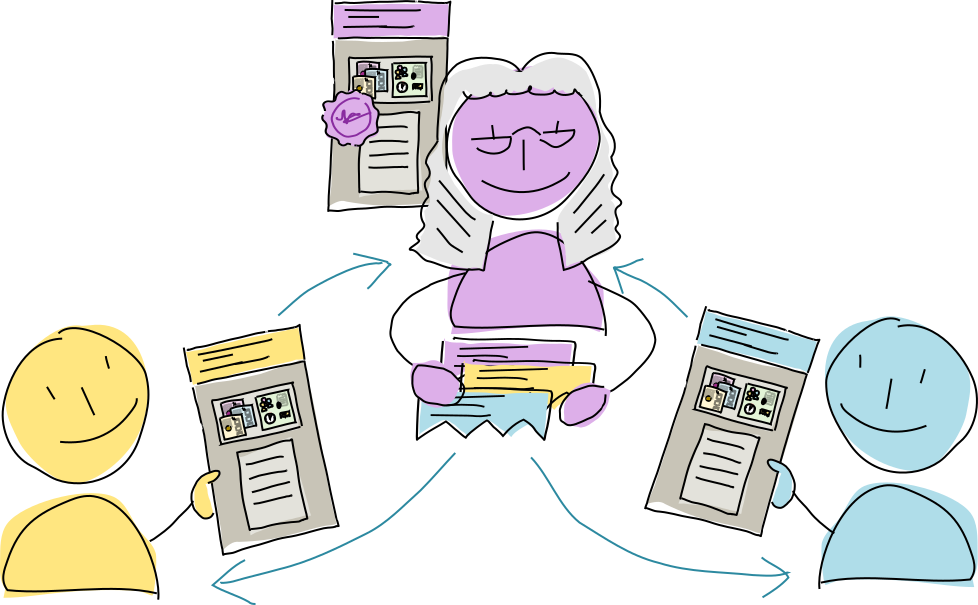

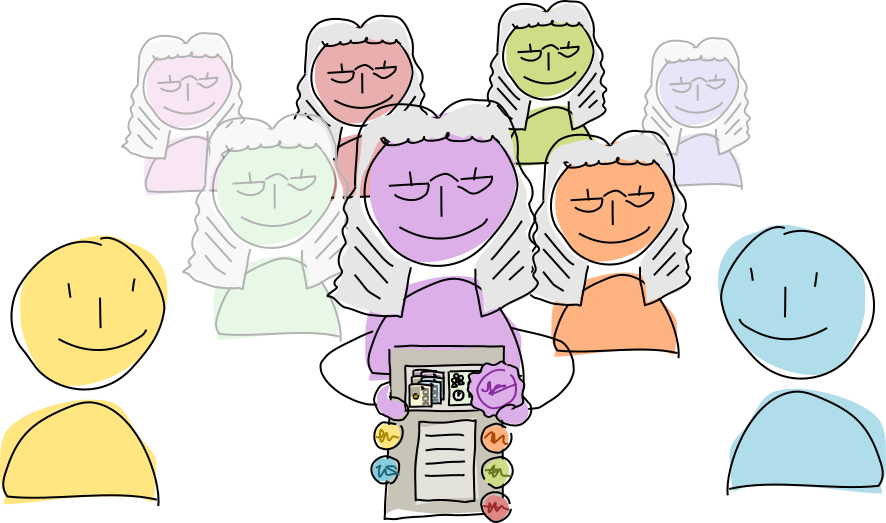

Enzymatic countersigning

Normally, counterparties publish their actions to a DHT neighborhood and hope that there are enough honest and reliable validation authorities there to collect and return a full set of signed actions to everyone. But this can put them at risk; if the neighborhood contains authorities who either are malicious, have slow network connections, or have inaccurate clocks, it’s possible for some counterparties to see all signatures within the time window while others do not. This would cause some to complete the session and others to back out, leading to inconsistent state on the DHT and even apparent evidence of source chain revisions.

The problem is compounded if one counterparty is able to collude with a neighborhood authority to collect signatures but not contribute its own signature to the session. This would cause all honest counterparties to reach the session timeout and cancel the countersigning process, only to have their full signature set revealed later when they’ve already written other records to their source chains, again creating apparent evidence that they’ve revised their source chains.

To counter this problem, the counterparties can nominate an enzyme. The enzyme is typically an agent that all counterparties can trust, with no stake in the transaction, who participates in the session only as a witness. It’s their job to collect all the signatures and send them to the other counterparties. The data they sign includes all signatures as well as their own. As the collector and final signer, they definitively determine whether the session was successful within the time period, and put their name to the presence of a full signature set.

Note that this still carries the same risks as allowing DHT authorities to be witnesses — an enzyme can still intentionally or unintentionally withhold the full signature set from one party until after the session timeout. But using an enzyme does locate all of the signature-gathering activity in one place, turning it into an all-or-nothing operation.

M-of-N optional witnesses

A countersigning session initiator can also nominate optional witnesses to sign the transaction. This can be used for anything that requires a quorum of signatures from a larger pool of potential signers, but shouldn’t fail if not all signers are available at the same time. The quorum can be specified in the preflight, but it must be greater than 50%. One of the witnesses must be an enzyme who collects all the required and optional signatures, in order to create a definitive list of which optional witnesses participated.

While this requires more network chatter, it can tolerate more hardware and network failure than a single enzyme. Although an enzyme is still required, the enzyme role (and, for that matter, the mandatory signers) could be rotated among the pool of witnesses.

One use of this is transactions that require multiple signing authorities, similar to a bank account requiring two signatures on all cheques. Another use is a ‘lightweight consensus’, in which a majority of trusted witnesses must confirm, before signing, that no counterparty is attempting to fork their source chain and no scarce resource is being allocated to two entities at the same time.

What about double spending?

If you’re familiar with blockchains, you might be wondering, how does countersigning deal with ‘double spending’? Countersigning, because it allows two or more parties to reach an agreement on something and publish the agreement, sounds like it might be an answer to this problem. The plain answer, though, is that it isn’t.

You could see a blockchain as simply a mechanism for determining what doesn’t exist; that is, a means of making a decision about what does exist in a distributed system and rejecting all other possibilities. Many transactional applications, such as currencies and transfer-of-title contracts (also known as non-fungible tokens or NFTs), depend on this feature to prevent one asset from being transferred to two different people simultaneously. Because there’s only one shared history, the recipient of an asset can be assured that an alternative transaction involving the same asset doesn’t secretly exist.

Holochain, on the other hand, merely equips all peers to detect source chain forks, which are the agent-centric equivalent of a double-spend, after they’ve happened. This lets peers avoid interacting with known bad actors.

In high-trust environments, this is likely to discourage forks simply due to the threat of ejection from a network. But in low-trust environments where counterfeit (‘Sybil’) agents are easy to create, or where people stand to gain from a fork even if they have to suffer the consequences, this might not be enough.

If your application needs something more, you can build in strategies to discourage, prevent, or detect a double-spend attempt as it’s happening. The simplest of these is the ‘lightweight consensus’ strategy mentioned earlier, in which an enzyme and/or optional witnesses act as trusted notaries. The continuity of their source chains means that any forks in the source chains of the parties they’re witnessing can be deterministically detected and rejected.

Key takeaways

- Countersigning allows two or more agents to reach a shared understanding of each other’s source chains in order for them to simultaneously write a single new action.

- Countersigning is an automated, non-interactive process that happens within a short time window, once all human agreements have been finalized.

- All participating counterparties must be online for the entire countersigning session.

- Countersigning begins with the sharing of a preflight, in which one party proposes a session time window, the hash of the entry to be signed, and the list of signers.

- Countersigning proceeds from preflight to the session once all counterparties have seen each other’s signatures on the preflight as expressions of commitment.

- Before writing the new record to their source chain, each party pre-publishes the action to the DHT, letting their expression of commitment become a public record.

- Once the DHT peers have collected the full list of actions, they broadcast them to all parties.

- Once each party receives all of their counterparties’ actions, they commit the new action to their own source chain and publish it to the DHT permanently.

- If a countersigning session times out before a party receives all counterparties’ actions, they may abandon the session. The DHT peers will also discard the pre-published entry and actions.

- A counterparty’s source chain is locked for the entire countersigning session time window, until the session succeeds or times out.

- One counterparty can be nominated an enzyme, who collects all signatures, signs the full signature set, and distributes the set to the other counterparties.

- Optional witnesses can be added to the session, a majority of whom must also sign it, and one of whom must be a non-optional enzyme.

- Enzymatic countersigning and M-of-N optional signers can be used to create various forms of robust, failure-tolerant witnessing, multi-signature transactions, and lightweight consensus.

- Countersigning is not for preventing double-spends; it’s only for atomically synchronizing a single write to multiple source chains.